*This is a guest post by Claire Bennett, co-author of

Learning Service: The Essential Guide to Volunteering Abroad.

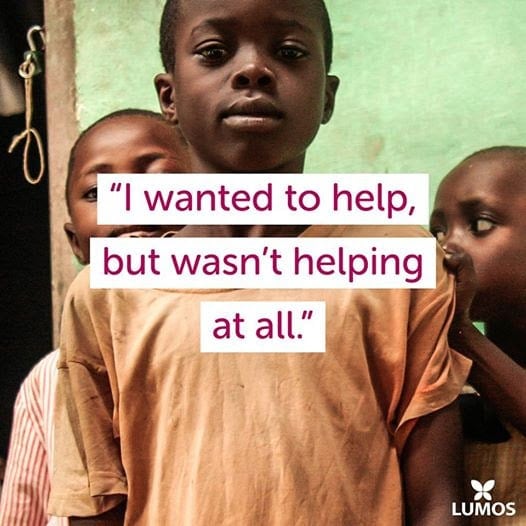

Photo Source: Lumos

I know what you’re thinking: “Stop writing such click-baity titles that you don’t really mean”, or “Look, maybe you can highlight some problems with it, but selfish is the wrong word.” After all, when we think about volunteering abroad it is often images involving children that come to our minds: a fresh-faced blonde girl standing at the chalkboard in a makeshift classroom, children huddled in rows on benches; a kid you went to university with giving a piggyback to a brown child in a rural setting in x-country (not sure where it is but definitely a hot climate); children clambering over benevolent foreign visitors to get in the selfie shot. These people might exist on a spectrum between altruistic and misguided, but if they wanted to be purely selfish they would be drinking margaritas on a cruise ship somewhere and not spending their precious vacation days doing some unpaid babysitting. Right?

Unfortunately, increased research into the field of voluntourism over the last decade has shed light on nefarious practices that are doing harm to the very causes and people that the volunteer is trying to help. And nowhere have the droves of evidence come out in more abundance than in the sector of volunteering with children overseas.

Backtrack one decade, to when I was living in Cambodia, when I became increasingly interested in the activities of the hordes of foreign volunteers who would show up in matching T-shirts ready to “save Cambodia, one child at a time.” Many of them saw themselves as the only solution to a desperate situation: the major tourist spots seemed to be teeming with homeless, orphaned or begging children, most of whom seemed to not have families or even an adequate number of carers. “Orphans” paraded in front of foreign audiences in nightly dance shows, lined up asking for donations outside bars, and accosted passersby to convince them to volunteer at their residences. Smiling children would swarm busloads of visitors, fighting for attention, affection and gifts. And the number of residential care centers for children (read: orphanages) were mushrooming, all of them competing for volunteers, donations and resources, and some of them keeping children in dilapidated and impoverished conditions.

What was causing the rise of this terrible situation, where separated, abandoned children were so desperate for care that they were latching on to any outsiders that came through? Was it conflict, disaster, extreme poverty? In fact, all these things were decreasing in Cambodia at the time (and still are), and the only observable thing that was increasing was the droves of tourists swooping in to save the day. I started to realize that this wasn’t just a response to the problem of the huge numbers of vulnerable children, but that it was also the cause.

In 2011 UNICEF released a report that found that the vast majority of children in orphanages had parents, and that the burgeoning numbers of such institutions was simply founded on a clever business model. On one hand parents were tricked into believing their child was better off in an orphanage than at home, and on the other hand tourists were seduced into giving donations that often went straight into the pockets of the corrupt owner. In other words, the support and donations flowing in from tourists and volunteers were direct factors in driving vulnerable families apart.

It turns out that this was a situation not unique to Cambodia. By the time this report was published I was living in Nepal, where disturbingly similar trends were just emerging. The numbers of orphanages were going up, just at the point when the numbers of orphans was in rapid decline. Again, the majority of the children living in institutions were found to have living parents, and 90% of orphanages were established in the top five tourist districts in the country. In fact, as this issue moved into the limelight, surprisingly similar stories were being uncovered across the world – in Haiti, Myanmar, Uganda, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Kenya to name but a few. Globally the number of children in orphanages that have living parents is thought to be between 80 and 90%.

There are manifold reasons why this is a terrible situation. Firstly, there are abundant stories from around the world of abuse and neglect in residential care institutions. Children in orphanages are often exposed to physical and sexual violence, kept deliberately under-nourished to solicit more donations, and forced to beg, work or dance to make a living. Even orphanages that try to take care of the material needs of the children in their care can do irreparable damage. Decades of research show that children raised in institutions instead of families develop psychological disorders, social problems and even developmental delays.

The sad fact is that tourists and volunteers visiting and supporting orphanages will always make the situation worse. Short term interactions with strangers – especially those uneducated in social work and who believe their main job is to offer love – can exacerbate attachment disorders in children who have already experienced abandonment and trauma. Added to this is the fact that the whole corrupt business model is founded on the demand from tourists for feel-good experiences and avenues to “help.” Quite simply, tourism dollars are fueling the separation of children from their parents and perpetuating a cycle of abuse – the exact opposite of what most of them intended. Uncovering the extent of this issue, among many other ways in which overseas volunteering causes damage, led me to campaign on these issues as a lifelong activist and was one of the motivating factors behind the book I co-authored, Learning Service: The Essential Guide to Volunteering Abroad.

So back to the question, despite all of the evidence that this kind of volunteering is doing harm, can we really say that it is selfish? After all, the harm is mainly unintentional, and the vast majority of volunteers engage in these activities with the aim of offering help. Unfortunately, this narrative of pure-hearted altruism is not the full story. Many volunteers may head off overseas without fully analyzing their own motivations. As well as the wish to contribute to a cause, volunteers may be looking for experience to add to a résumé, some cute pictures for their social media feeds, or simply a story they can tell at a party that will make them look like a good person. Certainly when celebrities engage in this kind of activity we can uncover (at best) some mixed motivations: remember Melania Trump dancing with orphans in Kenya, Kanye West handing out designer sneakers in an orphanage in Uganda, or the trend of Bollywood movie stars celebrating their birthdays in orphanages. Rather than anonymous acts of philanthropy, these were carefully-staged publicity events.

In fact, one of the reasons that volunteering with vulnerable children is so popular is that it feeds what has been termed the white savior complex. Children, especially “orphans” can seem like innocent victims, and “helping” them can seem so easy when they so readily offer instant gratification in the form of hugs and smiles. Other forms of volunteering, especially that which happens behind the scenes such as editing reports, preparing training materials or entering data into a spreadsheet, doesn’t offer the same quick fix of those feel-good endorphins – or the same access to photo opportunities. This is despite these activities invariably being of more use than the “playing” or “caring” that is usually undertaken by orphanage volunteers.

The bare truth of it is that there is simply no excuse for truly well-intentioned travelers to volunteer in an orphanage. Unlike a decade ago, when volunteers could be forgiven for not knowing that their actions may be damaging, there is now robust research, countless media stories, and high profile figures such as J.K. Rowling bringing attention to the issue. There has even been legislation restricting some forms of orphanage tourism in Australia – with the Dutch Parliament likely to follow suit and debates about it in the Commonwealth. If you don’t believe me about how widely covered this topic is, simply google “orphanage tourism” and see what comes up. Ultimately, we have to take responsibility for our actions, and if we engage in actions that cause harm because we are too lazy to take the time to research, then there is a strong argument to say we are being selfish.

So if we care about vulnerable children and want to do something to help, what can we do to try to ensure we are not being selfish? Here are some condensed points (all of them explained more fully in the Learning Service book!):

- Fully examine your motivations for volunteering. If you are honest, you will find that your motivations are not fully altruistic, and that you may be combining your desire to help with your learning goals, travel aspirations, or career plans. And this is totally OK – being honest about your range of motivations is not selfish; in fact it is key to ensure that you have realistic expectations.

- Research the provider and the project fully. Many volunteer projects are touted as a way to solve complex social issues such as poverty. Ensure that the project you are working on have evidence to prove they are making a real and sustainable change to the issue, not just pasting on a band-aid. You also need to ensure that the work you will do is in line with your values. If you need help with how to research a volunteer placement, we at Learning Service have made a downloadable tool to help.

- Ensure you have the appropriate skills for the job. Good volunteer providers go through a process of “skills-matching” which could include an application form, interview or selection day. A basic rule of thumb is that if you are not qualified to do a job in your own country then you will not be qualified to do it elsewhere.

- Don’t volunteer in orphanages. In fact, unless you have very specialist skills it is unlikely that any kind of volunteering directly with vulnerable children will be helpful, as they have complex needs which cannot be met by short-term help.

- Practice responsible photography. Posting images of children on your social media feeds, especially those with whom you do not have a close relationship with or perhaps whose parents have limited understanding of how photos are used on the internet, can be unethical. Instead, think about how you can use photography to highlight an issue without exploiting the subjects.

- Support children in families. There are many organizations out there that run family strengthening programs, to ensure that parents never feel compelled to send their children away. Other organizations work to reintegrate children who have been trafficked or held in abusive orphanages back into their families. Find ways to volunteer at or offer other support to these organizations.

I hope this post has convinced you to think carefully about your volunteering, and to take responsibility to ensure that the actions you take result in the impact you desire. We would love to discuss this topic more with you, please send your stories, thoughts and reactions to us! *

Claire Bennett is a co-author of Learning Service: The Essential Guide to Volunteer Travel. You can find out more about Learning Service from their website: www.learningservice.info or follow them on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

*PIN- IT! If you like this post and want to keep it for future reference, don’t forget to pin the image/s below on Pinterest!